Quentin Schultze asks many questions here that churches should be asking. Author of Habits of the High-Tech Heart: Living Virtuously in the Information Age (Baker, 2002), Schultze continues to study technological issues that affect worship planning and leadership. After reading “all of the literature I could find on technology and worship,” Schultze offers the following list of questions as a place to begin thinking, not as an exhaustive list. Worship committees, elders, worship teams, and the growing numbers of tech support teams in worship would do well to take these questions a few at a time and discuss them in their meetings. Schultze will lead a discussion on these questions at Symposium 2003 (see inside front cover).

—ERB

- Has worship in the Hebrew and Christian traditions always included technique, if not technology?

- Which aspects of worship should we define as “essential” practices (that is, good in and of themselves, regardless of the expected results), and which are “instrumental” (that is, normally directed toward an expected result)? Does such a distinction make sense or help us in talking about technology and worship?

- We know that all technological developments produce unintended consequences that can become more significant than the intended outcomes. What kinds of unintended consequences do we see emerging in the growing use of presentational technologies in worship? Are they good or bad consequences?

- Scholars of technology sometimes argue that the technologizing of human endeavors shifts the user’s focus on the means rather than ends. As Ellul puts it, the means become ends in and of themselves. Is this true in worship-related technologies?

- Other scholars suggest that human technologies over time redefine how the users view both human nature and the technological activities. Are worship technologies altering our view of what it means to be a person created in the image of God? Are they altering how we think of worship itself as a human activity?

- Technological innovation frequently leads to human idolatry of technology—a sense of the “awe and mystery” of the “power” of technology to improve (if not save) the world. Does this kind of idolatry occur with respect to worship technologies? To press it further, do users of such technologies tend to infer greater power to technique and less to God? (What would one conclude about this from reading the articles and advertisements in worship technology trade magazines?)

- Is it possible that some worship technologies are more compatible with particular Christian liturgical/theological traditions than with others? Or particular parts of the church year than others? Or particular phases in the life of a congregation?

- How might we define the “holiness” of worship with respect to technology?

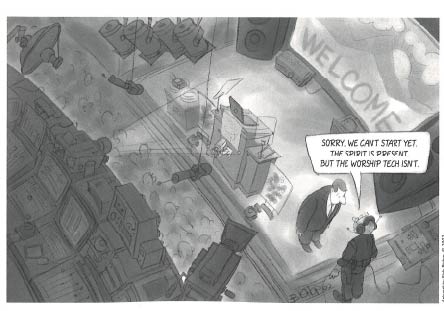

- Do new technologies “enfranchise” all members of a congregation, or do they tend to create new quasi-ecclesiastical differences in power and authority? To put it differently, are technologists beginning to dictate the way we worship in many churches?

- Do these new technologies over time become so institutionalized in liturgy that they are autonomous—beyond critique and charting their own courses as new innovations appear on the scene?

- What, if any, are the criteria that churches might use to access their use of worship technologies? Which of these criteria might be widely employed in society (perhaps goodness, beauty, and truthfulness) and which ones might be idiosyncratic to the essential nature and purposes of godly worship (that is, which ones would reflect the distinguishing marks of “holy” or set-apart worship)?

- What are the implications of the new technologies for church architecture and interior design? Do “technology friendly” churches also foster vibrant congregational fellowship and communal worship?

- One way of talking about the different approaches to technological innovation is to posit three alternative directions: adoption, adaptation, and rejection. Do these kinds of categories help us to make sense of how congregations might consider whether or not and how to employ new technologies?

- Frequently we laud the fact that technologies enable us to create larger “scales” of operation. Is the scaling of congregational size through new technologies something worthy of discussion?

- What kind of witness to the “world outside” is the use of cutting-edge technologies within the church?

- Worship always involves some type of focus—thematic, visual, textual, and so on. What happens to focus in services that rely upon extensive technology? What do members see, hear, feel?

- One major stream of thought in the philosophy of technology suggests that humans should always strive for “appropriate” use of technology in given situations. What is appropriate for worship? How can a congregation determine this?

- Liturgical renewal often seeks to reclaim vibrancy by getting back to the basics or core meanings and practices. Can we imagine this kind of purposeful renewal in the face of technological innovations as well? Can we reclaim the essentials of traditional worship through the process of technological consideration?

- How shall we think about worship technology in terms of stewardship of resources, given the seemingly unending costs incurred with repairing and replacing technologies?