A mother and father travel to meet their teenaged daughter, who is returning home after a year in Argentina. On the trip the parents snap pictures: (1) the departure, (2) a stop to swim in a mountain lake, (3) pictures of that lake shot from an overlook, (4) the airport, (5) the daughter’s arrival, and (6) the rainbow crowd of passengers disembarking the plane from South America.

When they get home, they sit down to organize their slides. They know the story told through these pictures will have more power if they organize it into a show, rearranging some of its moments. Although they visited the outlook after swimming, they place the panorama of the lake before the picture of them swimming in it, as if in anticipation. And they use digital formatting to set their daughter’s arrival against the background of her cross-cultural experience. They lay the image of her arrival over that of the rainbow crowd. The two pictures become one, a composite.

Christmas Cycle Slide Show

The way the Revised Common Lectionary (RCL) tells the story of Christ’s birth is like that slide show. By carefully arranging the banquet of images that the story serves up, the lectionary adds power to the message. Take a look at the readings for this year, Year B.

In this seasonal cycle, the RCL moves through a series of moments: (1) the coming of the Son of Man, (2) John the Baptist, (3) the Annunciation, (4) the birth of Jesus, (5) the Presentation, and (6) the visit of the wise men. You’ll notice that, like the pictures in the slide show the parents prepared, these images are out of chronological order. For example, the readings on John the Baptist precede the birth of Christ.

This reordering of the narrative sequence of Scripture may be disconcerting to those who love to tell the story as it is found in the Bible. Such telling has a long tradition in the Reformed churches. Indeed, the Westminster Directory instructs congregations to read through the Bible in a year’s time, chapter by chapter. While this directive is hard to follow to the letter, variations upon it are still found in Reformed congregations.

The church year, and the RCL readings that give it flesh, have a different aim. They seek to proclaim the good news by focusing on the coming of Christ, from his first coming in Advent to his second at year’s end. Like a slide show, the RCL organizes the telling of Christ’s coming—selecting moments, ordering them for effect, and relating images one to another.

Layered Meaning

As a slide show may use a number of pictures to capture each moment, the RCL supports the dominant image with images found in other texts. So, alongside the governing Gospel text, we find two other texts in support—one each from the Old Testament and the New Testament writings. A psalm (also suggested for each week), is traditionally sung after the Old Testament reading.

These supporting readings serve to focus and nuance the thrust of the dominant image. Thus the RCL does not seek to proclaim the coming of the Son of Man on the First Sunday in Advent, but rather counsels us to watch and pray for that coming. This slant on the image runs like a thread through the readings for this Sunday.

Finally, the RCL uses “advanced techniques” to relate images one to another. Just as the parents of the returning daughter laid her image over the rainbow crowd, so the lectionary lays images one upon another.

In Advent-Christmas-Epiphany, the lectionary uses this technique to set the birth of Jesus in the larger context of his saving work. For while the Christmas story warms the heart, it is not in itself saving. This birth is saving only because the child born is the one who will one day suffer, die, and rise again.

Take a look at Christmas Day, Proper I, for example. The RCL juxtaposes the prophecy of Isaiah 9 and the Lukan version of Jesus’ birth to a passage from Titus that proclaims Christ’s saving work in its totality. In doing so, it lays the shadow of the cross and the light of the cave upon the hope of the crêche.

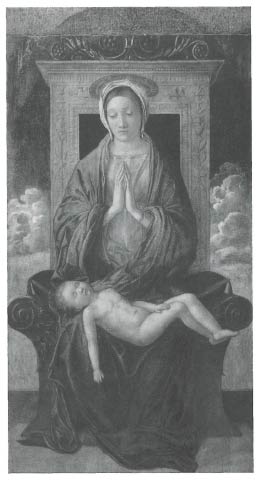

A painting by the Italian artist Giovanni Bellini (ca. 1430-1516) makes a similar move. Madonna Enthroned Adoring Sleeping Christ Child (1475) pictures the infant Jesus in the posture of the dead Christ in a pietà . The babe lies across the lap of Mary, body extended, head thrown back, right arm dangling down toward the ground, left arm laying across his loins. Just as this painting anticipates the death of Christ, even at his birth, so do readings in Advent set forth the fullness of our salvation. In the seasonal cycle surrounding Christmas, the RCL proclaims the good news through a series of images and their interplay.

Madonna Enthroned Adoring Sleeping Christ Child, 1475. Art by Giovanni Bellini (1430-1516). Tempera on wood. Accademia, Venice, Italy. Photo by Art Resource, NY.Used by permisssion.

| Day | Text | Image | Proclamation |

| First Sunday | Isa. 64:1-9 |

The Coming of the Son of Man |

Watch and Pray |

| in Advent | 1 Cor. 1:3-9 | ||

| Mark 13:24-37 | |||

| Second Sunday | Isa. 40:1-11 | John the Baptist | Prepare the Way |

| in Advent | 2 Pet. 3:8-15a | ||

| Mark 1:1-8 | |||

| Third Sunday | Isa. 61:1-4, 8-11 | John the Baptist | Messianic Age |

| in Advent | 1 Thess. 5:16-24 | ||

| John 1:6-8, 19-28 | |||

| Fourth Sunday | 2 Sam. 7:1-11, 16 | The Annunciation | Christ Is Coming |

| in Advent | Rom. 16:25-27 | ||

| Luke 1:26-38 | |||

| Christmas Day* | Isa. 9:2-7 | The Birth of Jesus; | Incarnation |

| Proper I | Tit. 2:11-14 | the Shepherds | |

| Luke 2:1-14 (15-20) | |||

| Proper II | Isa. 62:6-12 | The Birth of Jesus; | |

| Tit. 3:4-7 | the Shepherds | ||

| Luke 2:(1-7) 8-20 | |||

| Proper III | Isa. 52:7-10 | Word Made Flesh | |

| Heb. 1:1-4 (5-12) | |||

| John 1:1-14** | |||

| First Sunday | Isa. 61:10-62:3 | The Presentation | Holy Family |

| in the Season | Gal. 4:4-7 | ||

| of Christmas | Luke 2:22-40 | ||

| Second Sunday | Jer. 31:7-14 | The Word Made Flesh | Incarnation |

| in the Season | Eph. 1:3-14 | ||

| of Christmas | John 1:(1-9) 10-18** | ||

| Feast of Epiphany | Isa. 60:1-6 | The Visit of the | Manifestation of |

| Eph. 3:1-12 | Wise Men | the Son of God | |

| Matt. 2:1-12 |