Updated June, 2025

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Psalm 22, one of the greatest laments in the psalms, begins with this poignant cry of Christ on the cross. The Jews who had gathered at the foot of the cross (whether to mourn or to mock) would have heard these first few lines of the psalm and been led by their theological training to recall the psalm in its entirety. It is as if Jesus spoke the entire psalm as he hung in agony on the cross proclaiming both his profound identification with a suffering world and the unlikely victory his suffering would produce.

So as we begin our planning for the season of Lent, it is appropriate not only to return to the subject of lament, but also to turn to the subject of our suffering world. Psalm 22 is a good place to start as we examine how biblical lament soothes the suffering and disrupts the comfortable.

Lament provides an avenue for the oppressed to proclaim justice without taking vengeance into their own hands. It allows the suffering to appeal to a higher authority. It proclaims God's ultimately triumphant reign in the midst of suffering and oppression.

Who Should Lament?

It may seem obvious to say that those who are suffering must lament. In neighborhoods of the world where people are struggling with sickness, oppression, and poverty, lament is inevitable. But an understanding of biblical lament as an honest cry to a good, powerful God—a cry that recognizes that a given set of circumstances is not aligned with God’s character and purposes, a cry that expects an answer, and therefore leads to peace, hope, and even joy—transforms our understanding of what lament accomplishes in these contexts.

Lament provides an avenue for the oppressed to proclaim justice without taking vengeance into their own hands. It allows the suffering to appeal to a higher authority. It proclaims God’s ultimately triumphant reign in the midst of suffering and oppression—giving hope where otherwise there would be no hope.

In his book In the House of the Lord: Inhabiting the Psalms of Lament, Michael Jinkins uses the example of the songs of deep sorrow sung by slaves in America: “These sorrow songs performed two tasks which the psalms of lament also performed: They put their oppressors on notice that the hand of justice will not always be stayed from the execution of its terrible commission; and they held God responsible for a deliverance that was beyond their own power” (pp. 37-38). By crying out to a just, good God, those suffering under injustice are no longer helpless. Lament gives the oppressed an avenue of strength, an element of hope, and a means to joy—no matter how dark the situation may appear.

That the suffering church continues to include lament in its gathered worship is essential, but I’m guessing that the majority of those reading this article are, like me, within the cozy confines of the comfortable church. While we all experience some suffering and pain in our lives, our lives are rarely threatened by anything but sickness or accident. We may be deeply moved by images of disaster on the news, we may even try to meet the needs we see through financial contributions, but the injustice that threatens usually threatens someone else.

If I am warm, well-fed, healthy, safe, and sheltered, is there really any need for me to lament? If I myself have no reason to cry out to God, why is it important that I do so?

Identification with Christ

It is important to lament because Christ lamented. I must cry out to God on behalf of a suffering world because Christ, in the midst of his suffering, cried out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” By crying out the beginning of Psalm 22 on the cross, Christ was also crying out, “He has not despised or scorned the suffering of the afflicted one” (v. 24).

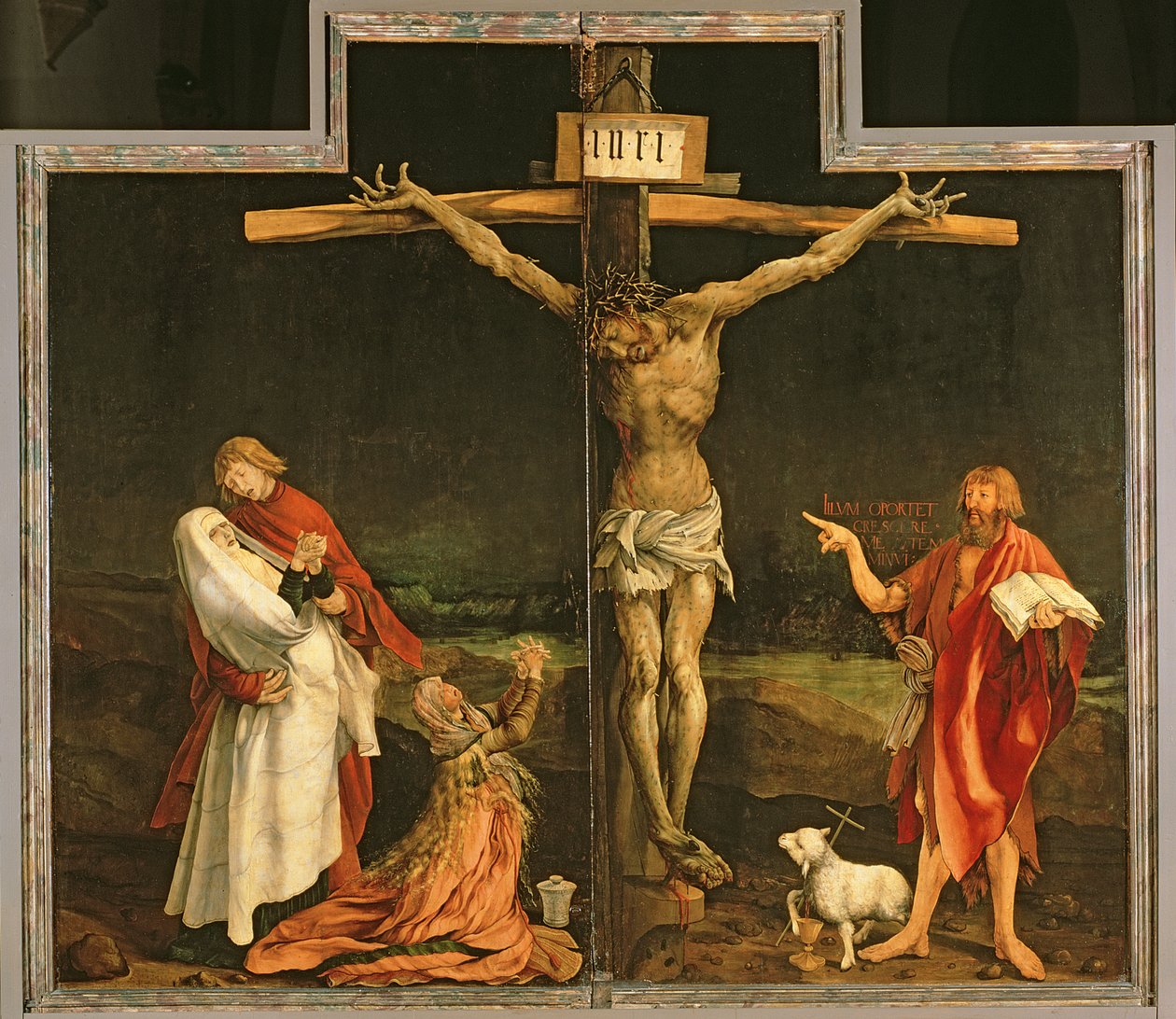

The Isenheim Altarpiece, painted by the German artist Matthias Grünewald, is perhaps one of the most riveting portrayals of the crucifixion. Grünewald painted it for the Monastery of St. Anthony, which specialized in hospital work, specifically the treatment of skin diseases. The central panel of the altarpiece portrays Christ in agony on the cross. His hands and feet are distorted painfully. His body is covered with sores. Imagine lying before that altarpiece, your own body covered with sores, suffering, perhaps dying. What comfort to know that not only is God with you in your suffering, but that he too has endured suffering!

Grünewald’s visual statement is both simple and profound: Christ identified himself completely and irrevocably with those who suffer.

Surely the body of Christ should do the same.

Addressing Suffering with Wealth

Often when a wealthy church includes an acknowledgement of a specific world need in its gathered worship, the call to action, and therefore the congregational response, is to give financially.

Giving from our wealth to address a financial need elsewhere is necessary and right, but unfortunately it can sometimes have a negative side effect. Often it results in a feeling of lifted responsibility—we feel that we’ve done our part and can dismiss the situation from our minds. Our money, no matter how much that money is needed, is not going to address the problem unless we also cry out to God on behalf of the suffering. Without the identification with our hurting world that lament provides, we can no longer preach the message of the cross, nor be in full communion with a God who is justice and righteousness.

The Crucifixion, Mathias Grunewald, picture taken from Die Kreuzigung, vom Isenheimer Altar, ca. 1512-15

Dangerous Posture

If Christ is aligned with those who suffer, then with what or with whom is the comfortable church aligned? Do we see the cross as merely a symbol, or can we affirm the truth of Grünewald’s Isenheim Alterpiece? Can we identify with the Christ in this gruesome portrayal? If not, we need to reexamine the heart of our faith, for perhaps we are worshiping the status quo rather than our dangerous, suffering God.

In our gathered worship and in our congregational and individual lives, we need to walk a fine line of contentment. Like Paul, we want to “learn the secret of being content in any and every situation” (Phil. 4:12). But at the same time we don’t want to be content with this world in its current state. We are called to push toward something better—toward the fullness of the kingdom of God and toward the day when God swallows up death forever, wiping the tears from every face and removing the disgrace of his people from the earth (Isa. 25:8).

We who live amid the wealth of the Western world cannot be content to uphold the status quo. We must lament, we must cry out on behalf of those who are carrying far heavier burdens than ours—for if we do not align ourselves with those who are suffering, if we cannot identify with them, we fail in the task to which God has called us.

Call to Action

Lament’s cry for justice flows naturally from the lips of the downtrodden. It is a cry that should issue more readily from the lips of the well-fed, the safe, and the comfortable.

Lament can wake the comfortable church to the reality of a suffering world, encouraging the church to align itself with Christ alongside the marginalized and those who suffer poverty, sickness, and injustice. Lament is an encouragement to action, because through it we call upon the justice and person of God, and are thus drawn into alignment with the kingdom of God. And the kingdom of God is never stagnant.

In his book For All God’s Worth: True Worship and the Calling of the Church, N. T. Wright describes this relationship between lament and action:

To believe in the Trinity is to believe that God came in Jesus to the place where the pain was greatest, to take it upon himself. It is also to believe that God comes today, in the Spirit, to the place where the pain is still at its height, to share the groaning of this world in order to bring the world to new life. But the Spirit doesn’t do that in isolation. The Spirit does it by dwelling within Christians and enabling them to stand, in prayer and suffering, at that place of pain. . . . We stand with those Christians who are at the place of pain right now, continuing through their tears to bear witness to the suffering love of the true God; and we pray for strength to say prophetically to our own government, and to other people’s governments, and to the United Nations, that there is a different way of ordering international affairs, and that we must seek and find it with all urgency (pp. 30-31).

—Used by permission of Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. All rights reserved.

In our gathered worship, we must pray, with Christ on the cross, the words of Psalm 22. We must follow this sacred prayer down into the depths of despair—allowing the images to draw us into other lives, in other places—speaking the words out loud for those whose mouths are too cracked with thirst to do so. We must follow this sacred prayer to its glorious conclusion, cutting through the darkness of this world with the glorious light of a victory yet to be fulfilled, but already accomplished: “It is finished.”