Roy Hopp describes the step-by-step process he follows to compose hymn tunes and explains how composing new tunes can help fill liturgical "gaps."

I began writing hymn tunes the same year that I began directing my first church choir. I was looking for hymns that would serve as choral closings for a service, and I grew frustrated. Although I found some excellent evening hymns, they were set to some very disappointing tunes. So I brashly decided to do something about it: I composed my first hymn tune for "The Day Is Past and Over," a song I found in The English Hymnal.

That was just the beginning. When I discovered that the choir liked my hymn and that it served well as a choral closing, I wanted more like it. So I looked for other "serviceable" texts that could use new tunes. Before long I had composed my first five hymn tunes—all of them choral closings written for the choir of the Princeton CRC in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Since then my interest in hymn composing has broadened. In the past years my choirs have sung newly composed introit hymns, communion hymns, mission hymns, hymns of prayer, hymns of assurance, and a very effective hymn paraphrase of the Ten Commandments.

Step by Step

My greatest inspiration for writing hymn tunes is the desire to fill a liturgical need, to provide something fresh and new for the worship service. But inspiration only goes so far. When composing hymns, most musicians follow a fairly technical, step-by-step process. To give you some idea of how I, and many other composers, go about it, I've described the procedure in the following paragraphs.

Step 1. The composer begins with the hymn text, working to understand it fully. The purpose and focus of the text then guides the composer to reflect a similar purpose and focus in the hymn tune. The mood of the text, poetic accents, and significant words affect musical decisions such as the choice of mode (major, minor, etc.), the choice of meter (3/4, 4/4, etc.), and the placement of the musical climax.

Step 2. Once he or she understands the hymn text, the composer is ready to go to the organ or piano and work on the hymn tune. This process, which often involves a lengthy cycle of rejecting, rewriting, and accepting musical ideas, is governed by certain rules of composition. These rules, or guidelines, are not absolutes, but they do provide a fairly predictable framework, and they separate the composer of the hymn tune from other composers. All composers, of course, follow guidelines. But the guidelines a hymn composer follows are unique—partly because of the audience. As a group, these people—a congregation largely made up of untrained singers—have neither the skill nor the training to sing music that is too complicated. The composer must keep that in mind while, at the same time, not underestimating these men, women, and children.

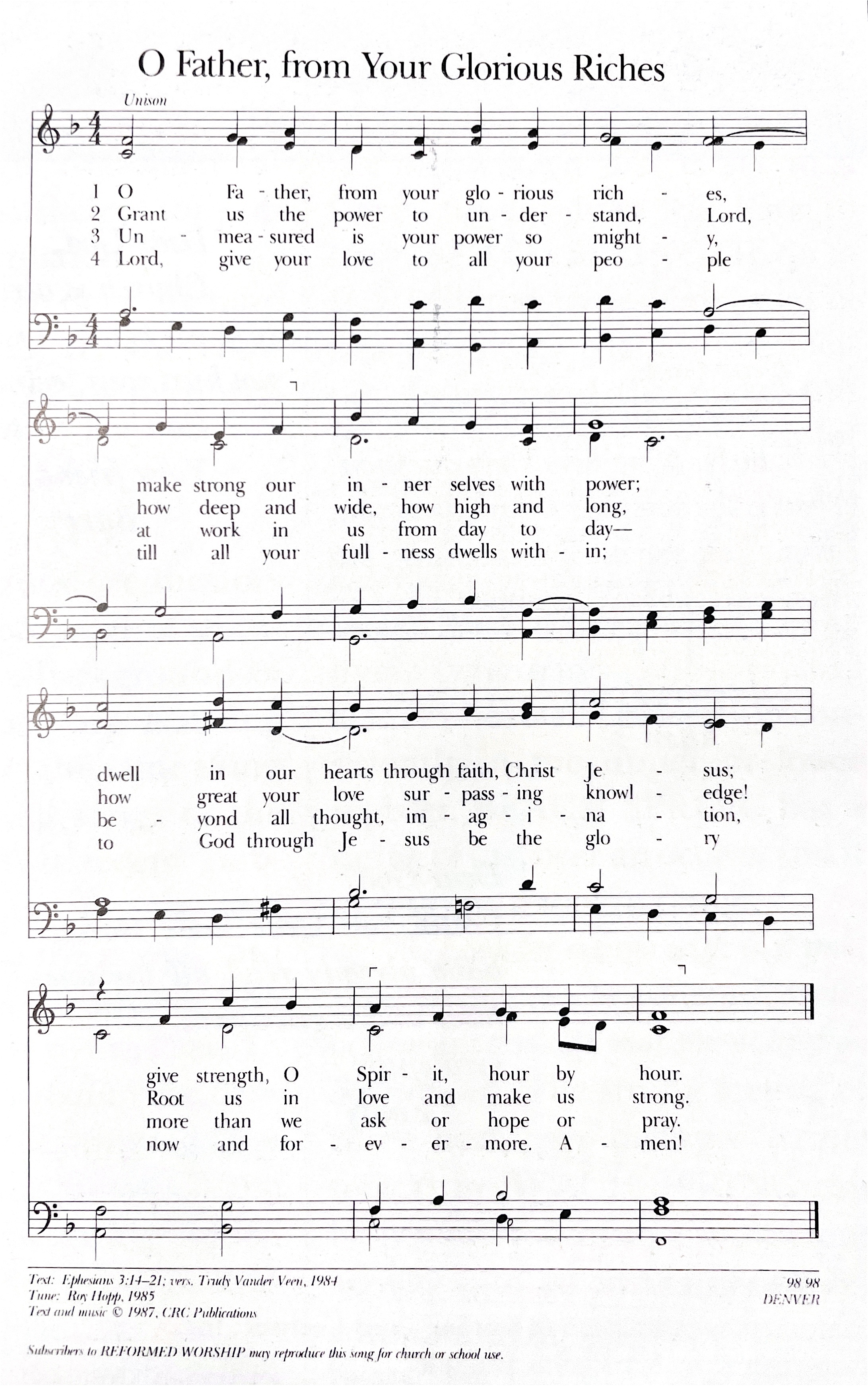

The four guidelines I consider important can be illustrated through my own work on the tune DENVER, set to "O Father, from your Glorious Riches," a text written by Trudy Vander Veen, a friend of mine who lives in Denver.

- The melody must be simple enough for a congregation of untrained singers to sing. A primarily stepwise melody with a judicious use of leaps and repeated notes is the norm. The range of the melody must be a comfortable one (from middle C to the second D above).

DENVER spans an octave (D to D) and is further strengthened by the natural flow of the predominantly stepwise melody.

- The rhythm of the melody should closely match the rhythm of the hymn text. A reading of the hymn text using the rhythm of the melody should result in an effortless rhythm that propels the text forward.

The meter of "O Father" is iambic (pairs of unstressed/stressed syllables). The stressed syllables fall on the first or third musical beats. However, at times the first syllable of a line (st. 4) calls for more stress; then a longer note is provided.

- The climax of the text should coincide with the climax of the melody. After the climax of the text has been determined (ideally in the same place in each stanza), the composer must try to create a climax in that same place in the tune. The climax of the tune could be set to a note that is higher (tonic accent) or longer (agogic accent) than any other note. Often the note that marks the climax of the text and tune is both the highest and the longest note of the melody.

The tune DENVER has two points of climax: notes at the beginnings of the third and fourth lines (with the leap up to C) coincide with words that benefit from the extra emphasis that the tune provides, especially in the first two stanzas.

Step 3. The third step in the process is the critical stage of self-evaluation. After I've written a hymn tune, I often find it valuable to set it aside for a few days. Then I come back to it and review what I've written. Sometimes I'm confronted with some unsatisfactory composing that needs major revision, but usually I find that just a note or two require change.

Once I've approved the tune myself, I often have the choir sing and critique it for me. Then, if I can find an appropriate place for the song in worship, the choir sings it as part of a service. If the congregation also likes the hymn, I encourage them to learn it and sing it with the choir.

"A New Song"

If a hymn is especially well received, the composer may want to try to get it published and thus make it accessible to a larger body of Christians. We are living in an age of increased interest in hymnody, an age when almost every major denomination is producing a new hymnal; many of these denominations are looking for new hymn tunes and will willingly consider submissions. Composers should also consider entering their hymn tunes in contests sponsored by the Hymn Society of America and many individual churches; the winner of a hymn contest may be in a good position to get some of his or her tunes published.

Composing a successful hymn tune is not an easy task. It requires a creative mind, a thorough knowledge of the craft of composition, a sensitivity to the hymn text, a knowledge of the capabilities of the singing congregation, a great deal of discipline, and a good measure of patience. If you can coordinate all of these attributes into the creative effort of composing a hymn tune, your rewards will be great. You will be numbered among the thousands of composers and poets who gave to the church and to the Lord a "new song" to sing.